My Journey to Ketamine

I became aware of several physicians administering intrathecal (IT) ketamine infusions in late 1990. They were dosing 50 to 200 micrograms per day for non-malignant chronic pain. Intrigued, I sought any existing clinical justifications. Lisa Stearns, MD, due to her wealth of knowledge treating chronic pain (cancer pain, specifically), was one of the first physicians I approached on the matter. Dr. Stearns was a strong advocate for intrathecal pumps. Because of her experience with cancer pain, specifically, she expressed being a proponent of IT ketamine infusions for her patient base. She stated that utilizing it in the last 90 days of life was common in her practice, and considered this medication an essential option for her patients.

These early inquiries, as well as subsequent clinical observations, shaped my deep conviction for ketamine as a viable and vital agent for relieving chronic pain, specifically in patients with cancer. Having stated this, I have also seen it used effectively in non-malignant patients through low-dose (<200 mcg/day) infusions. Notwithstanding the anecdotal evidence, I’ve found the use of intrathecal ketamine for treating non-malignant chronic pain to be rare. What might be the cause for this? To begin with, published studies on its use in the pain pump are scarce. Secondly, the issue of toxicity is often raised and should certainly be addressed before incorporating it into any treatment regimen. Following is a brief review of ketamine, as well as a discussion of studies and the topic of toxicity.

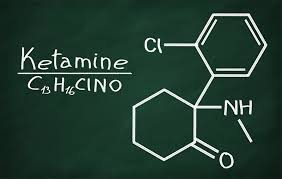

Ketamine Hydrochloride

Approved by the FDA in 1970, ketamine acts primarily as a noncompetitive antagonist of the N- methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor for glutamate, a major excitatory neurotransmitter within the central nervous system (CNS). It was originally indicated as an anesthetic induction agent with doses ranging from 1mg/kg to 4.5mg/kg IV, and exists in two enantiomers: S & R structures. The S enantiomer has greater potency due to its affinity for the PCP binding sites on the NMDA receptor. Structurally related to phencyclidine, ketamine has a lower incidence of hallucinations and minimal effect on respiratory function. Some studies suggest that ketamine de-sensitizes excitatory receptor systems within the CNS. It has also been known to produce a dissociative sensation that some individuals exploit for non-medical use cases. Other reported effects include elevated blood pressure (as opposed to most anesthetics), and bronchodilation.

Existing Studies

The Polyanalgesic Consensus Guidelines (2017), widely considered to be the primary guide for treating patients intra-spinally for chronic pain (1), references ketamine IT use for chronic pain. Sator-Katzenschlager et al, studied one patient with chronic pain treated with ketamine (Ketanest ™) that was administered intra-spinally via the Medtronic SynchroMed pump. The initial regimen consisted of ketamine 31.5mg/day and morphine 10mg/day. The subsequent ketamine dose was increased to 47.2mg/ day for a total infusion duration of 24 days. The patient received significant pain relief without psychotropic or neurological side effects (2).

Another case report in the British Journal of Anesthesia, Bernath J., et al, studied the treatment of neuropathic pain, secondary to urethral carcinoma. The patient had received oral and IV therapy, neither of which were clinically effective for pain relief. An infusion pump was surgically implanted, and ketamine (Ketanest ™), morphine, and clonidine were administered into the reservoir for infusion. The patient’s pain relief was satisfactory over 10 weeks with infusion rates as follows: ketamine 22.5 mg/day, morphine 36 mg/day, and clonidine 300 mcg/day. This treatment regimen was effective without the side effects of arterial hypertension and psychomimetic alterations or neurological dysfunction (3). Another case report documenting the treatment of neuropathic cancer pain with ketamine by Vranken, JH et al, revealed significant pain relief with in the final three weeks of life for a 77-year-old female with adenocarcinoma caecum. This patient received 40mg/day, along with morphine, bupivacaine, and clonidine; achieving good pain relief and no observable toxicity symptoms (4).

A Note

I would like to highlight that the above studies deal with end-of-life treatment. I believe ketamine to be clinically advantageous for cancer pain where other pharmaceuticals have been ineffective during the last days of life. However, I reiterate that I am aware of its use in low doses to treat non-malignant chronic pain. This low-dose approach (often <200 mcg/day) has had no observable side effects and has achieved great pain relief.

Intrathecal Ketamine and Toxicity

Intrathecal ketamine toxicity is a common concern. But, limited publications reporting such toxicity exist. Of those published, there is controversy related to the cause of histological changes. One case report, where patients received 67.2mg/day, reveals histological changes within the medullary tissues, in nerves and leptomeninges, but no necrosis, hemorrhage or signs of demyelination. Another case report showed pathological changes of the subpial spinal cord vacuolation of a terminally ill patient receiving 5mg/day for three weeks, but the precise cause could not be ascertained.

Yet another study revealed that spinal cord lesions occurred after utilizing intrathecal ketamine with chlorobutanol. It appears, though, that all clinicians were uncertain if the cellular changes were a result of ketamine, the preservative (benzethonium / chlorobutanol), or some combination of other agents infused (morphine / bupivacaine, hydromorphone) (5,6,7). Undoubtedly, ketamine should not be used cavalierly, but toxicity concerns should be tempered.

Conclusion

We engage physicians about their IT-prescribing habits to understand both what type of chronic pain they treat regularly, as well as to understand their unique approach to treating said pain: is the pain focused, or widespread? Is it nociceptive or neuropathic? Malignant or non-malignant? The right patients and circumstances compel us to mention the use of ketamine as an effective agent. This suggestion is often met with intrigue, but we find it has been given little consideration up to that point. However, it has helped patients achieve better pain relief and quality of life. Its intravenous counterpart is already widely accepted by the pain management community. We hope this article sparks some curiosity, if not interest, in ketamine as an agent for treating chronic pain, malignant or otherwise, intrathecally.

- Deer et al: The Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference (PACC): Recommendations on Intrathecal Drug Infusion Systems Best Practices and Guidelines. Neuromodulation 2017; 20: 96-132

- Sator-Katzenschlager, S et al: The Long Term Antinociceptive Effect of Intrathecal S (+) Ketamine in a Patient with Established Morphine Anesth Analg 2001; 93: 1031-4

- Benrath, J et al:Long-term intrathecal S (+) ketamine in a patient with cancer-related neuropathic pain. BJA 2005; 95(2): 247-9

- Vranken JH : Treatment of neuropathic cancer pain with continuous intrathecal administration of S (+)-ketamine. ACTA Anaesthesiol Scand 2004; 48: 249-52

- Stotz, M, Oehen, H, Gerber, H: Histological Findings After Long-Term Infusion of Intrathecal Ketamine for Chronic Pain: A Case Report. J Pain and Symp Management. 1999; Vol 18 No. 3: 223-8

- Karpinski, N et al: Subpial vacuolar myelopathy after intrathecal ketamine: report of a case. Pain 1997, 73: 103-5

- Malinovsky, J: Is Ketamine or Its Preservative Responsible of Neurotoxicity in the Rabbitt. Anesthesiology 1993; V 78 No. 1: 109-15

Leave A Comment